Stephen Prina

by Jonathan Griffin

On a dance mat in a cavernous rehearsal space in downtown Los Angeles, the actor Abbott Alexander put on a battered green bowler hat, last worn onstage 33 years ago. Nearby, two drummers perched behind their kits and, to the side, two dancers stretched against the wall.

Directing the proceedings were Stephen Prina, a conceptual artist and musician, and Anita Pace, a choreographer; they, along with the protean artist Mike Kelley, devised this elaborate performance, “Beat of the Traps.” It has been staged only four times: in 1992, in Vienna and Los Angeles.

For a five-decade survey of Prina’s work, opening Sept. 12, the Museum of Modern Art in New York has commissioned its revival, part an extensive musical performance program that includes a new composition and a rearrangement of a Mozart string quartet scored by Prina in 1976 when he was just 21.

Like all Prina’s art and music, “Beat of the Traps” reconstitutes cultural artifacts from the past, with fresh sounds, images and forms in the unfurling present. The ensemble had just three weeks before showtime, scheduled for Sept. 18.

“One more time!” Prina commanded.

Since studying at CalArts in the late 1970s with conceptual artists such as John Baldessari, Douglas Huebler and Barbara Kruger, Prina, 70, has developed what he describes as a “post-conceptual” and “project based” art practice across multiple mediums.

There’s no recognizable look or sound to a Prina project; perhaps this is why he is not known more widely, despite representation by Petzel Gallery, Sprüth Magers and Galerie Gisela Capitain, and an emeritus professorship at Harvard in art, film and visual studies.

Kruger, who became a close friend after he assisted her class at CalArts, called him a “brilliant” and “wonderfully generous teacher.” “He pays attention to subcultural concerns, popular adorations and all that’s in-between,” she said. (In the 1990s, Prina drew attention for offering a film theory class on the oeuvre of Keanu Reeves.)

Most of his MoMA survey, “A Lick and a Promise,” consists of performances staged in various locations around the museum between now and Dec. 13. Just four of his artworks hang in the galleries. One, from 1993, is a clock that chimes at each hour with one of the top 13 singles on the Billboard chart for the week ending Sept. 11, 1993, when it was made. Another installation packs an entire gallery with ink-wash drawings of the same dimensions as monochromes by historic artists including Kazimir Malevich and Robert Ryman.

Prina’s work is sometimes discussed as “institutional critique” — that is, art that focuses on the exclusionary systems of power and connoisseurship maintained by the institutions in which it hangs. But Prina does not scorn museums, or the artists they exalt.

“There’s deep love there,” he told me when we met recently in his studio in Glendale, Calif. The question he’d asked himself as a young artist, he said, was, “How do you identify a love object and then also differentiate yourself from it?”

He has never been shy about borrowing from other artists or musicians. Frequently, he’ll declare his references outright, often in titles; other times he hides them in plain sight.

The first time I heard Prina perform a solo gig with an acoustic guitar at Sprüth Magers in Los Angeles, in 2018, it took me a while to realize that all the songs he was playing were covers — among them, a heartfelt rendition of Joni Mitchell’s “A Case of You,” a favorite that taught him, he said, “that a pop song could be art.”

Conversely, when I listened to his 1999 record, “Push Comes to Love,” I had to search the liner notes to be sure that all the songs are originals. (More or less, that is; one track, “The Devil, Probably,” sources its lyrics from subtitles in a Robert Bresson film.) “To me, all art is derivative,” Prina told me. “Every artwork is an act of cultural appropriation, which is neither positive nor negative, as far as I’m concerned.”

For Prina, the copy is not a form of counterfeit, in the way his colleague Sherrie Levine’s rephotographed Walker Evans picturesmight (simplistically) be understood. In his remakes and translations, Prina pays homage while asserting his individuality.

“What Prina is doing in these performances is literally putting his own body on the line,” said Stuart Comer, chief curator of media and performance at MoMA and the organizer of “A Lick and a Promise.” This is quite different, he added, to acts of photographic appropriation that were typical of Prina’s peers in the Pictures Generation.

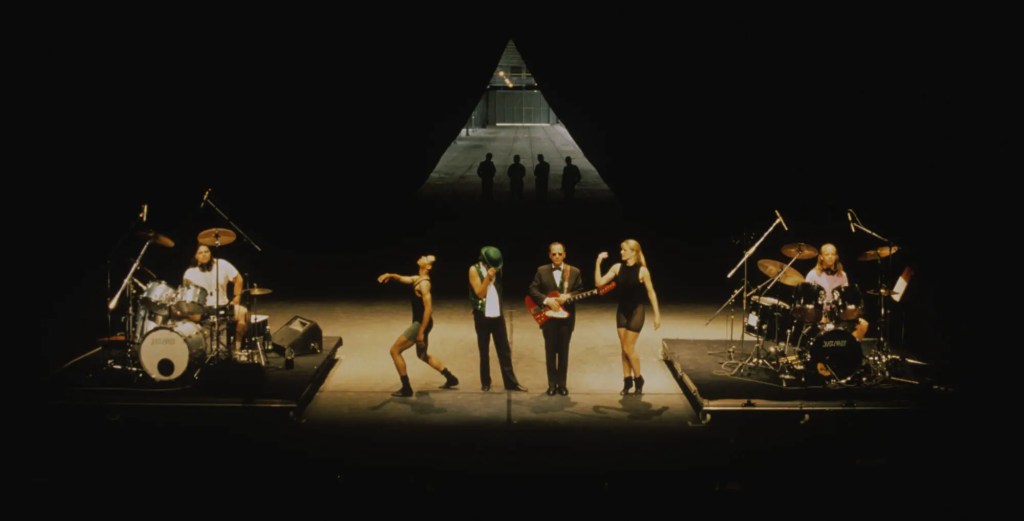

Prina appears in “Beat of the Traps” too. In dark glasses and a green bow tie, and with a red Gibson Firebird guitar, he’ll sing a cover of whichever song is at the top of Billboard’s Hot 100 chart on the week of the performance. (He’ll have two days to learn it before opening night.)

That move reflects the influence on Prina of Fluxus artists such as John Cage, who allowed chance to dictate the form of their work. It also enables “Beat of the Traps,” a postmodern period piece incorporating music from the late ’60s and ’70s, to endlessly update itself to the present.

The project began over drinks in the early ’90s, when Pace suggested collaborating with Prina. One of them — neither can recall who — offered the idea of choreographing a 1980 composition by Prina for two drummers based on numerical sequences. Ideas piled up. When Pace told Kelley (her partner at the time, with whom she sometimes collaborated) of the idea, Kelley asked if he could contribute too.

“I think the idea was to build a drum-dance-music-song-performance that would be kind of an epic theater performance piece,” Pace said, wryly. Doubling — a theme that runs through much of Prina’s work — was a structuring conceit.

Kelley, who died in 2012, wrote four monologues, each summoning the excessive personas of a star drummer: John Bonham of Led Zeppelin, Keith Moon of the Who, Mitch Mitchell of the Jimi Hendrix Experience and Paul Whaley of Blue Cheer.

These are delivered, dramatically, by Alexander in a green bowler hat and green sequined vest. Elsewhere in the performance the drummers Jonathan Norton, known as Butch, and M.B. Gordy (who both participated in 1992) recite iconic drum tracks from those bands, in duets played just one beat apart. Led Zeppelin’s “When the Levee Breaks,” as you’ve never heard it before.

The effect is the auditory equivalent of watching a 3-D film without glasses: occasionally legible, but often, as Prina put it, “like the ceiling is falling in.”

In rehearsals, I watched as the dancers, Freeda Electra and Jon Baldwin, emulated Pace’s jerky, eclectic choreography, which draws on styles from ballet to rock. They were dancing not to the track being played — Prina’s 1980 “Etude for Percussion (Square Root Function II)” — but to “Happy Jack” by the Who.

“I don’t know if you can say it makes perfect sense,” Pace said. When I inquired why, in the performance’s thunderous encore, the drummers abandon all prior logic by hammering out overlaid rhythms from tracks by Captain Beefheart and Albert Ayler, Prina replied cheerfully, “Because we can!”

Despite its cerebral, structuralist underpinnings, Prina’s work is ultimately directed by intuition. Acknowledging the inescapable influence of one’s predecessors, he shows, does not mean surrendering one’s creative sovereignty.

First published: The New York Times, September 11 2025